October 8, 2025

di Francesco Ramella

In 1825, the first public railway line from Stockton and Darlington in the UK was opened to traffic. For more than half a century, there was a vigorous development of rail that outstripped animal transport on land and river transport. At the end of the century, three new actors made their appearance: the car, the truck and the airplane.

Rail enterprises began to suffer. Passenger and freight traffic revenues declined, money that was supposed to be spent on maintaining the network was used to cover operating losses, the quality of services worsened resulting in a further drop in traffic and revenues. Most of the private companies were heading toward bankruptcy. But the European governments decided otherwise, and, except for a few local lines, they nationalized the entire sector. Since then, a government-owned company – British Rail in the UK, SNCF in France, Deutsche Bahn in Germany, Ferrovie dello Stato in Italy were running most of the services. Despite substantial subsidies that covered (and still cover) much of the production costs and the high taxation of the road, however, the market share of the railways continued to decline.

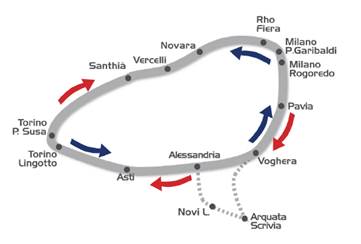

In the 90’s the UK privatized the sector but, after a few years, the infrastructure returned to government control. At the same time, the EU approved a directive aimed at overcoming the public monopoly and allowing private companies to enter the services market. In Italy, the first company to seize this opportunity was, in 2010, Arenaways, a small company founded by a former railway worker, strived to provide a ring service between Milan and Turin with no subsidy.

The “ring” service between Turin and Milan

The traditional distinction between “first” and “second” class had been eliminated, replaced by a single “UNICA” class. The quality level of the trains was higher than that typically found in local transport and comparable to that of long-distance services.

Additional services included free Wi-Fi, a small shop for purchasing goods, and a laundry service. Access for disabled passengers was available on all trains without the need for prior notice. Refund conditions were more generous than those of the incumbent: a bonus was granted for delays starting from thirty minutes, directly credited to subscribers’ cards.

It was also possible to purchase tickets on board the train without a surcharge.

On November 10, 2010, five days before the start of services, the Office for the Regulation of Railway Services issued a decision, prohibiting Arenaways trains from stopping at any intermediate stations. This was because the passenger rail transport service provided by Arenaways on the Turin-Milan route is of a ‘regional’ nature and compromised the economic balance of the [heavily subsidized] public service contract of the railway company Trenitalia.

Following this decision, Arenaways opted not to implement the “ring” service but instead operated only a direct connection between Turin and Milan, with four daily train pairs. The schedules allowed by the network manager were not particularly attractive. Arenaways was forced to cover the Turin-Milan route in just under two hours, compared to a minimum technical time of one hour and thirty-five minutes. Morning trains arrived after 9 a.m., making them less than convenient for most commuters.

As was easily predictable following the regulatory office’s decision, Arenaways’ passenger numbers fell far below initial projections. In its first six months, the company generated approximately 2 million euros in revenue against a projected 12 million for the first year, incurring a loss of just under 4 million euros.

On August 1, 2011, the Turin Court declared the firm bankrupt.

Fifteen years later, Arenaways, jointly with Renfe the Spanish state-owned rail company, is back but the story is a completely different one.

Arenaways will provide services on a secondary line in Piedmont that was closed to traffic in 2012 when just 800 trips were made on weekdays. The goal set by Arena is to reach 1,000 passengers. Before the closure of the line, Trenitalia received an annual subsidy of 2.1 million euro (2.6 million today, adjusted for inflation) to operate the service. Arenaways has been granted an annual subsidy of 4.5 million for ten years, 73% more than what the Region gave the public monopolist. On top of the 45 million in train subsidies, another 47 million, to be amortized over about thirty years, is needed for the refurbishment of the track. The total annual cost is around 6 million, which, divided by around 300,000 trips, implies a per-trip subsidy of 20€. A commuter traveling 250 days a year will be subsided for an amount of 10,000€.

Many other Italian regions are now asking the company to repeat the operation on their secondary lines.

Faced with these numbers, the company’s CEO stated: “it’s better to have a company that pays salaries every month than one forced to close like 15 years ago.”

It’s indeed better for the company, its employees and the passengers but it’s worse for the taxpayers: business as usual in the railway sector.