23 febbraio 2023

di Francesco Ramella

This time is not about the size, shape and texture of peas or plums. It’s about one of the main economic sector in the EU: about 13 million Europeans work directly or indirectly in the automotive industry and its turnover represents 7% of the total GDP. More importantly, cars (and trucks) are by far the dominant mode of transport in all countries, comprising on average 81% of all passenger transport. There is no doubt that the decision by the European Parliament to outlaw all sales of non-zero vehicles from 2035, which in fact bans new petrol and diesel cars from, will impose additional costs on most consumers.

This provision is part of the larger plan to reach net zero CO2 emissions by 2050. A goal to be achieved whatever it takes according to the European MPs. As economist Tyler Cowen put it: “we cannot simply keep on producing increasing amounts of carbon emissions for centuries on end. We thus need some trajectory where — at a pace we can debate — carbon emissions end up declining. Climate change is not in fact an existential risk, but it could be a civilization-destroying risk if we just keep on boosting carbon emissions without end. I don’t know a serious scientist who takes issue with that claim”.

The peculiar nature of the problem (very high number of potential victims and negative effects of the present emissions persisting for decades or centuries) casts doubts on the possibility of implementing a property-right based approach. Rather, a revenue-neutral carbon tax seems to be the least expensive feasible policy. Setting a “price” on carbon is nevertheless better than direct regulation of emissions because there are many ways to reduce emissions. Should consumers use less energy? Should they shift consumption toward products that use less energy to produce? Should we try to produce energy from low-emission sources or non-emission sources? Should we try to remove CO2 after the carbon is burned?

Putting a “price” on carbon does, in fact, give people an incentive to do all of the above at the minimum possible cost. The central planner cannot do it because he lacks the information required and right incentives.

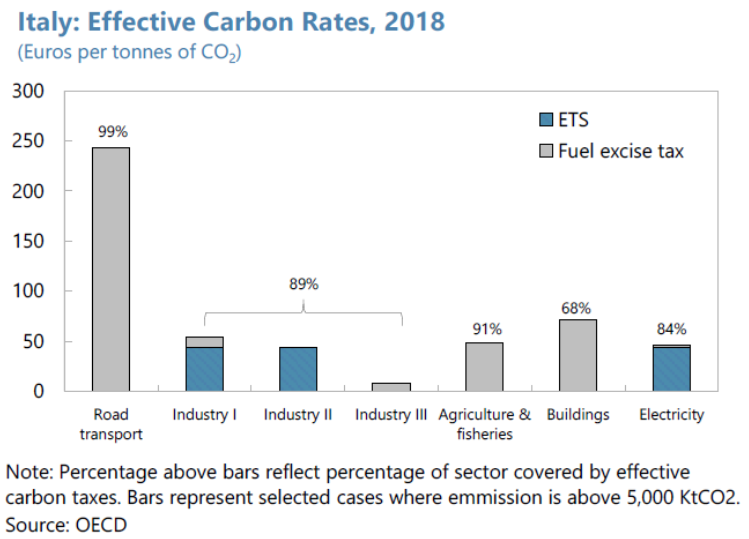

Now, back from theory to reality. In Europe the fuel excise tax is equivalent to a carbon tax of about 250 € per ton of CO2.

If we consider the whole fiscal income from motor vehicles, each ton of CO2 emitted is taxed about 800 €. The carbon “price” that leads to the desirable emissions should be equal to the social cost of carbon, that is the damage done at the margin by emitting more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

The literature on the social cost of carbon is large and estimates vary. Most studies conclude that the cost is below 200 € per tCO2. The European Commission’s own evaluation is 150 €. The Biden administration has been using an interim value of $51. Last October, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed increasing it to $190. Put differently, there is no need for further regulation. Lower or zero emissions vehicles should be simply taxed less than petrol and diesel ones.

We don’t know whether this approach leads to zero emissions in 2050: would zero emission vehicles be less expensive to operate (all things considered) than non-zero after taking into account the carbon tax? It depends upon the evolution of costs and consumers’ preferences on both sides. If the answer is negative, then it means that the target is too strict: costs are higher than benefits.

An assessment of the Europe’s climate target for 2050 carried out by Richard Tol concluded that “the total cost of greenhouse gas emission reduction could be 3% or more of GDP. The benefits would be only 0.3% of GDP, a benefit-cost ratio of one in ten. The marginal costs and benefits give the same message. The marginal costs of greenhouse gas emission reduction would reach €500/tCO2 by 2050 while the marginal benefits would be less than €150/tCO2, a benefit-cost ratio of three in ten.”

In a sentence, it’s highly probable that the ban will make us worse off.

If the European Union does not change its mind about the ban of non-zero emissions vehicles, it should at least scratch another of its plans. For example, it should stop investing in new infrastructures and subsidizing services in order to shift some passengers from road to rail. Bruxelles is pursuing this policy since more than thirty years: in vain. The increase of transport demand since the 90s has been largely satisfied by cars and truck. Now, if we are rushing to zero emissions vehicles, what has been an impossible task will also become a useless one. The only winners will be bureaucrats and rent seekers. Don’t be surprised if they continue to support it.

In fact, just a few days after the decision by the European Parliament, Frans Timmermans, the EU’s head of climate change policy, in an interview to the Bild newspaper, said that “we don’t need new motorways. We should invest heavily in the railways”.